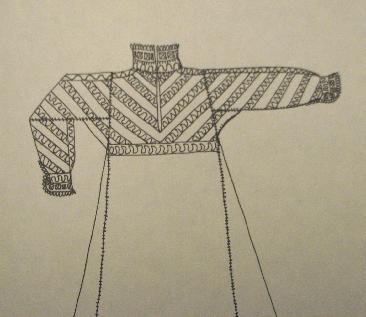

The Wadham College Shift

An Elizabethan shift c. 1600

|

|

| The front design |

|

Located in Wadham College Oxford, this shift is traditionally said to belong to Dorothy Wadham, the college's benefactor, who died in 1610.1 If the shift is really hers (which sadly, is very unlikely, since the shift was donated in 1913, and there is no evidence it belonged to the Wadham family), this would definitively place the garment within the Elizabethan period, but even if it is a random surviving shift, the pattern and embroidery design clearly place it as made between 1580-1620. It was restored in the 1990s by the Textile Conservation Centre at Hampton Court.2

A shift with a remarkably similar design can be seen at the Museum of Costume in Bath , corroborating its probable date of creation. The Wadham shift is embroidered in pale lilac silk (possibly once a little darker)3, whereas the similarly designed (but not as attractive!) shift in Bath is worked in black silk.

Shifts and shirts in the Elizabethan period (and for some time later) were made by women4 - the simple block construction required no special fitting techniques (such skills were closely guarded by the tailor's guilds) other than general fitting of the neck and wrist bands. Even with these, the fashion for wearing the neck open and the cuffs turned back meant that exact fitting was really not vital, though an ill-fitting shift would be a sign of a poor seamstress. Embroidered shifts lack the gold thread and spangles of Elizabethan outer garments and accessories, but they could be very beautifully decorated.

|

Shirts and shifts (considered undergarments by the Elizabethans) were made of linen, as is the Wadham shift. The high-necked construction of the shift is typical of the period; men's and women's shirts and shifts were almost identical, the main difference appears to be that men's shirts were shorter and slit on the sides, whereas women's shifts were longer and included side gores for added fullness (this can be seen in the Wadham shift).5

Personally, I think that towards the end of the 16th century, high necked shifts were more popular for women as an everyday garment than the low shift and partlet. A partlet is fiddly and awkward to pin into place by oneself, and while the argument can be made that most women would have someone to help them dress, the convenience of the high shift argues for its greater use. In addition, many pictures of working women appear to show them in high-necked shifts, most notably in the broadside "The Bellman of London", which shows a number of women with open doublets or jackets, revealing the shift.6

|

The original shift is made of linen, cut in the typical pattern of shifts of the era.7 The pieces are sewn together with pale lilac silk thread, using a detatched buttonhole stitch, a process where the pieces are hemmed with linen thread, then buttonhole stitched and stitched together using the embroidery silk.8

Several garments in the Victoria & Albert Museum that date from the same era are sewn with the same seaming technique, which produces an attractive and decorative seam.9

The shift is edged with lace at the collar, cuffs, and hem. Though the collar and cuff lace is larger and more expensive-looking than the hem, the hem lace could sometimes be seen, if the wearer was receiving visitors at home; Elizabethans had a different concept of dress than today, and the term "nightgown", "nightdress", or "nightcap" referred to informal clothes worn in the evening after the formal clothes of the day were taken off. The loose or fitted jacket would often be worn over an embroidered "night" shift.10 Certainly the wearer would enjoy showing off the shift, as it is still beautiful 400 years later, and must have been stunning when new.

The fairly narrow nature of the lace at the neck might suggest that it was intended as a nightgown, but it is equally plausible that it was intended to be worn with a larger detatchable ruff. Lace was a visible sign of wealth, and most of the surviving shirts and shifts of this period feature some sort of lace, even if it is quite small.

|

The embroidery design consists of bands laid out in a chevron design on the sleeves and torso, the bands filled with a simple but effective twisting vine motif of leaves and berries. The sleeves and body bands are not exactly lined up, but they are close enough to appear so at a casual glance.11 The exact matching of patterns, especially for embroidered pieces, was not considered neccessary back then, and since it would often be worn under other articles of clothing, exact matching wasn't considered as essential as a rich and well filled-out pattern.12

The underarm gussets continue the sleeve pattern layout rather than being embroidered with a separate motif as can be seen in the Warwick shirt, where the gusset has a single centered motif.

|

The reproduction: First of all, I want to say up front that this shift was not made from scratch. This piece was an older linen shift of mine, patterned with inset sleeves instead of gusseted straight sleeves and a curved, non-gussetted collar, so the basic construction is not period. I had originally intended this as a small project to keep me busy during idle moments at SCA events when I was at a stage of working on the Maidstone jacket that couldn't be transported easily.

Honestly, this was just supposed to be a quickie. A few hundred hours later, I realized that nothing I do ever seems to work out that way. If I had known it was going to be this much work, I'd have started with a period shift. Ah well - live and learn (and it gives me an excuse to make another embroidered shirt - probably for my husband).

The embroidery is the interesting bit, and what I've focused on here. I'm just being honest with you guys about the shortcomings of the project.

|

|

| The original embroidery design |

|

I modified the embroidery design somewhat; since I was working with a partially disassembled machine sewn shift (hey, at least it's linen), I didn't worry about the seaming technique. I also changed the shape of the vine leaves; my experience with jagged-edged leaves (and carnations) has been that I can't get the proportions right, and they end up looking like grade-school "art" drawings. I changed it to a heart-shaped leaf and used a template to ensure that each leaf stayed the same size and filled the space correctly.

Proportion and "filling the space" are important in Elizabethan design; the modern eye sees empty space as a way to set off the effect of the embroidery, but the Elizabethan eye sees that same space as something that needs to be filled. By using a template, I was able to keep the design consistent with the original.

|

|

| sleeve detail, with lace |

|

I drew out the design using a waterproof ink pen (micron 0.1), and typically for me, I couldn't find a picture of the front of the shift, only the back, so I guessed at the front layout. Fortunately for me, when I did finally locate a picture, my guess turned out to be correct; the back has a vertical center band, and the front does not. The neck opening of the shirt on the original comes down almost to the bottom of the embroidery (typically, women's and men's shirts of the time have very large openings, almost down to the bottom of the breast-bone)13, and a vertical band would be divided and awkward.

I lined the upper body so that the inside stitching wouldn't show when the shift is worn open (which it will be, most of the time), added more linen to make it longer (it doesn't match, but that's period - if the bottom wore out, or got stained, or if the shift was made over for a new wearer, whatever linen was available would have been used), and found a pretty decent commercially produced lace to look like bobbin lace.

I used black silk instead of the original lilac/purple because I had a bunch of black silk on hand, and this was supposed to be a quick cheap project.

In fact, it did end up being pretty cheap. I had to buy one more cone of large black silk, and several spools of thinner silk for the fill, but the immediate cost was still under $50. Recycling old clothes is a very Elizabethan thing to do; even Elizabeth I had many outfits altered and remade into other garments. As with many other embroidery projects, the major investment has been my time - the end time on the project was 625 hours.

I should have made a handkerchief.

|

Mistakes - I made a few.

And finally, what I did wrong. A couple of major things stood out, and both were the result of not paying proper attention during the layout of the embroidery pattern, and taking a rather slapdash approach to the whole thing. Overall I'm still pleased with the way it turned out, but I should have taken more care at the beginning. Anyway - the mistakes:

- The back design is not quite centered - I eyeballed the center line instead of measuring it (like you should), and as a result, it's slightly off-kilter. This is the less terrible mistake. The bad one:

- The sleeve chevrons are upside down - they're supposed to go the other way so that they line up with the lines on the body (as in the sketch of the original). My husband was very nice about it, and pointed out that the lines line up when I have my arms down, but still, it's a major mistake.

Today's lesson? Don't be so eager to get something done that you don't pay attention. Good thing this was just a quickie project, right?

Right?

|

Notes:

1. Wadham College, Oxford, England. The shift is on display in the college library and can be viewed by appointment.

2. Wadham College Alumni Newsletter, Summer 2003.

3. Elizabethan Embroidery, George Wingfield Digby, Faber and Faber Ltd, 1963. Plate 35.

4. The Art of Dress, Jane Ashelford, National Trust Enterprises Ltd., 1996. pp. 29-31.

5. Elizabethan Embroidery.

6. Images of the Outcast: The Urban Poor in the Cries of London, Sean Shesgreen,

7. Historical Fashion in Detail, Santina Levy and Susan North, V&A Publications, 1998. Page 150.

8. Elizabethan Embroidery.

9. Ibid.

10. The Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

11. Elizabethan Embroidery.

12. Multiple embroidered garments from the period show the same lack of concern for absolute lining up of the patterns on the individual pieces; the fashion for detatched embroidered seams also negates the need for perfect matching .

13. There are many, many pictures of women in shifts with very low openings, and a number of surviving shifts show the same thing.

|

|